In the accompanying publication, Van Oost’s grounded practice is described as “evoking the intrinsic relationship between feminism, inhabitation and nature, weaving her own wool to make wall hangings and clothing”. As the informative exhibition at Galway Arts Centre showed, she began making animist textures with wool before shifting to working with nylon tights. A selection of what she produced was shown, with the aid of digitally restored, former analogue slides that form part of Ireland’s Women Artists Action Group, and a rather poetic film about her life and work, made by Michael Holly and Mieke Vanmechelefilm about her life and work, made by Michael Holly and Mieke Vanmechelen. On the wall, seeming like a spectral reclamation of Van Oost’s spirit in her later days, was a materially degraded, personally expressive work by the artist, recovered last year from a garage in Killarney, loaned by its owner Brian Bowler for this exhibition. It is suspected it might have given by the artist in exchange for repairs to her car.

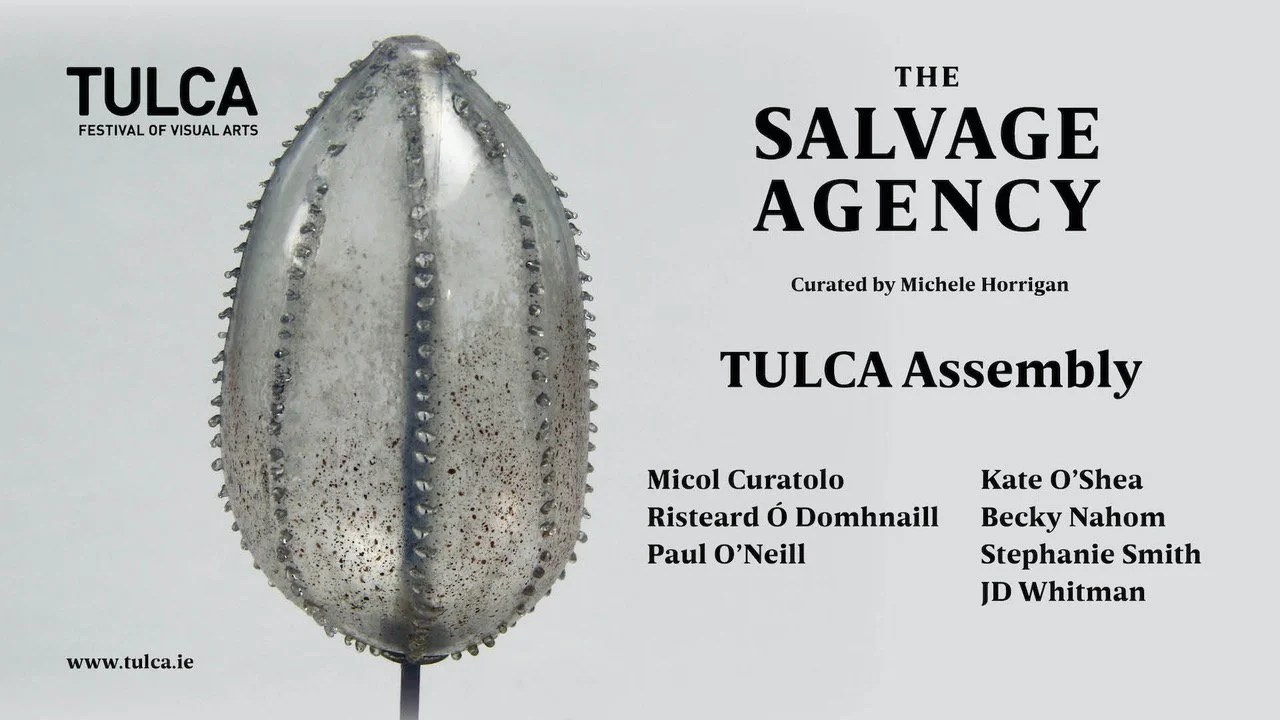

We learned, too, from a process of reconstruction in the film, aided by Grace Wells, a poet and artist who stayed with and interviewed Van Oost during the 90s and who has loaned archival materials for this exhibition, that the sensibility that led to Van Oost finding a space of artistic refuge in Kerry, where she also developed a significant garden, was shaped by her dark early childhood experiences in Belgium. Van Oost became an Irish citizen in 1985. The sensitive mediation of her story within the context of a programme themed around the topic of The Salvage Agency became, in turn, exemplary of the timeliness of this curatorial concept.

That became manifest also on several levels in the group show (of works by nine artists) at The Printworks gallery, where Barron, whose practice is entirely based on found, natural and otherwise often overlooked materials, and who was first brought to cultural attention by Horrigan and Lynch, got pride of place. He works with sticks, in effect, that he finds in the habitat around where he lives in Askeaton, unearthing and untangling them from their deep roots, or picking them up around the Shannon estuary, then refining them in his own way, while retaining the specificity of their character. The artefacts he creates are described either as walking sticks (sometimes with the addition of other dimensions such as deer horns for handles), or as “priests”, the vernacular name for bits of wood used in fishing to hit the catch over the head.

An award-winning film about Barron (also by Holly) was on display. This brought us on a memorable walk along a disused railway line with Barron, who drew us into the living experience of his reality of finding things that might be transformed by him into works by a blending of organic happenstance and rummaging in the undergrowth. Shot with care, the film reveals Barron’s articulate simplicity and directness that stands on its own, needing no explanation. Meanwhile, the chance to see some of his sticks in a context closer to their origins, seamlessly displayed among the plurality of paraphernalia in Freeneys fishing tackle shop in the nearby high street, remains one of the highlights of my visit.