‘To go to Ballinasloe’ was once a familiar turn of phrase for many in the West of Ireland. Synonymous with the stigma of a mental health crisis and subsequent institutionalisation, it was often said in low, hushed tones about a friend or relative, only to be quickly followed by a jolt of dreadful recognition. The town of Ballinasloe in County Galway is home to St Brigid’s Hospital, which was established in 1833 as the Connacht District Lunatic Asylum. As such, the town came to be almost solely associated with the hospital and its purpose, and ‘to go to Ballinasloe’ became a shorthand for someone experiencing a mental health crisis or committal to psychiatric services. After the introduction of deinstitutionalisation in the late 1980s, the hospital entered a period of decline and finally shuttered its doors in 2013. The building itself is a large, limestone structure that dominates the surrounding landscape, designed in the shape of an ‘X’ with a central tower, which sits like a proud steeple. Still to this day, many families in the region have a connection to the hospital, either as patients, staff or relatives of either.

It is not just Ballinasloe that is used as a metonym for such diagnoses and their negative perception – many places in Ireland have garnered this reputation, including Grangegorman, Portrane and Our Lady’s Hospital in Cork. The fear that these places once provoked is wholly appropriate when one considers Ireland’s dark history of incarceration. In the twentieth century, Ireland imprisoned more of its population than any other country in the world. In the 1950s, one per cent of people living in Ireland were institutionalised and uniquely, the largest cohort were in state-controlled mental health facilities.1 In 1951 Ballinasloe had a population of 5,596, of whom 2,078 were patients at St Brigid’s, thus forming the basis of the town’s socio-economic identity. Given the scale of incarceration, it is inevitable that many of those living in such institutions did not in fact have mental health, intellectual or developmental disabilities. Rather, people were committed for a wide range of reasons, including inheritance disputes, as a means of control, to disappear family members and to relieve the pressures of poverty and migration.2 The lasting impact of these institutions has weighed heavily on how many disabled people relate to a sense of place, and their feelings of home and belonging. In this way, the state’s response to disability and its treatment was a defining political force in the formation of the early Irish state and its sense of modernity.

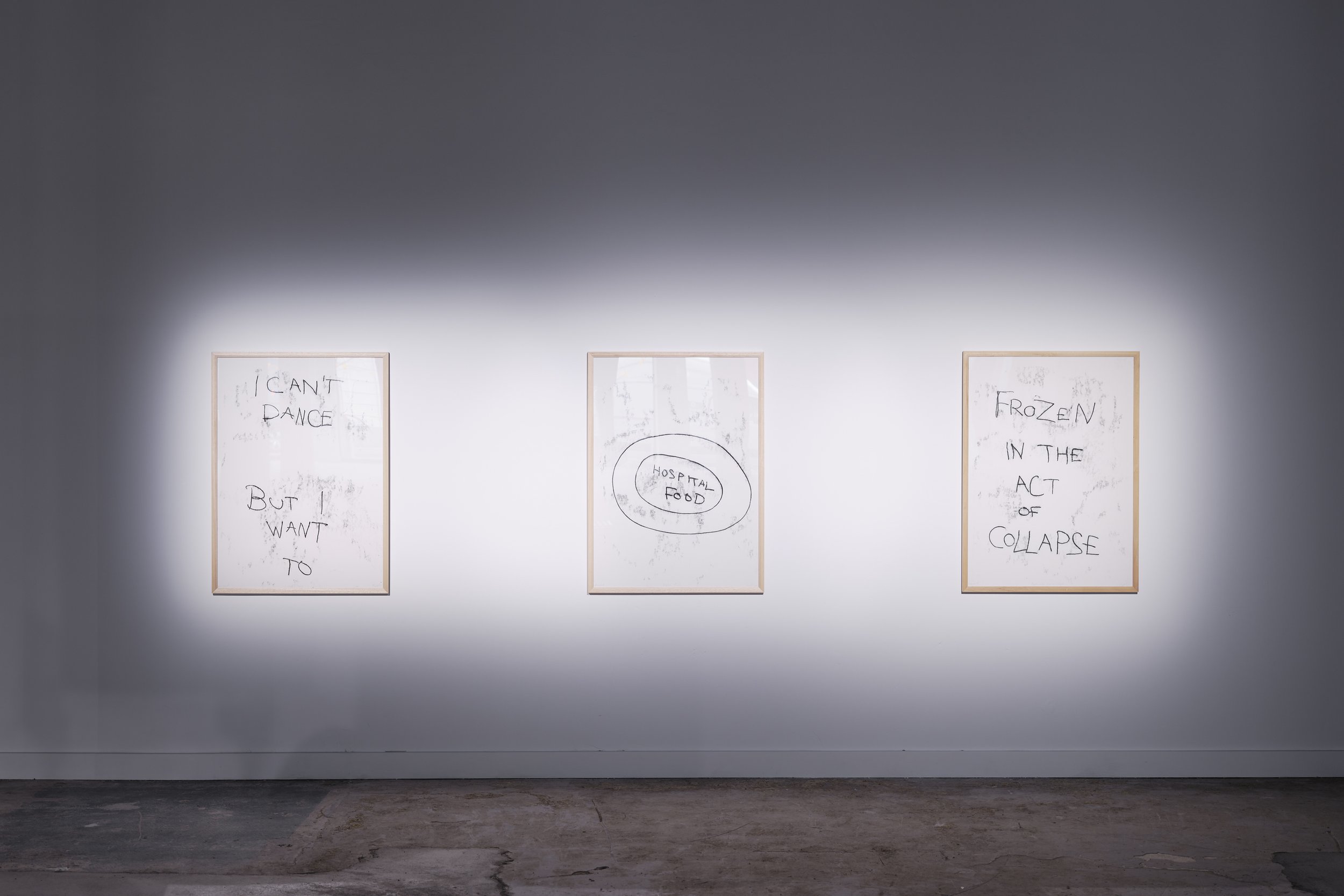

It is within this legacy of mass medical incarceration that the 21st edition of the TULCA Festival of Visual Arts took place in Galway (3rd–19th November 2023) FIG.1 FIG.2. Taking its title, honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, from an Irish folk cure for what was described as ‘madness’, the festival responded to the evolving experiences of disability and medicine in the West of Ireland and elsewhere.3 It reflected on the role and legacy of institutions such as St Brigid’s and how ideas of health and treatment can shape both landscapes and communities. The works of art and texts also examined how these places have affected people on a personal level: how medicine shapes our connection to place and the intimacy of access. This article discusses a number of works exhibited in the festival in relation to these legacies that speak through anti-ableist,4 abolitionist and disability justice perspectives.5

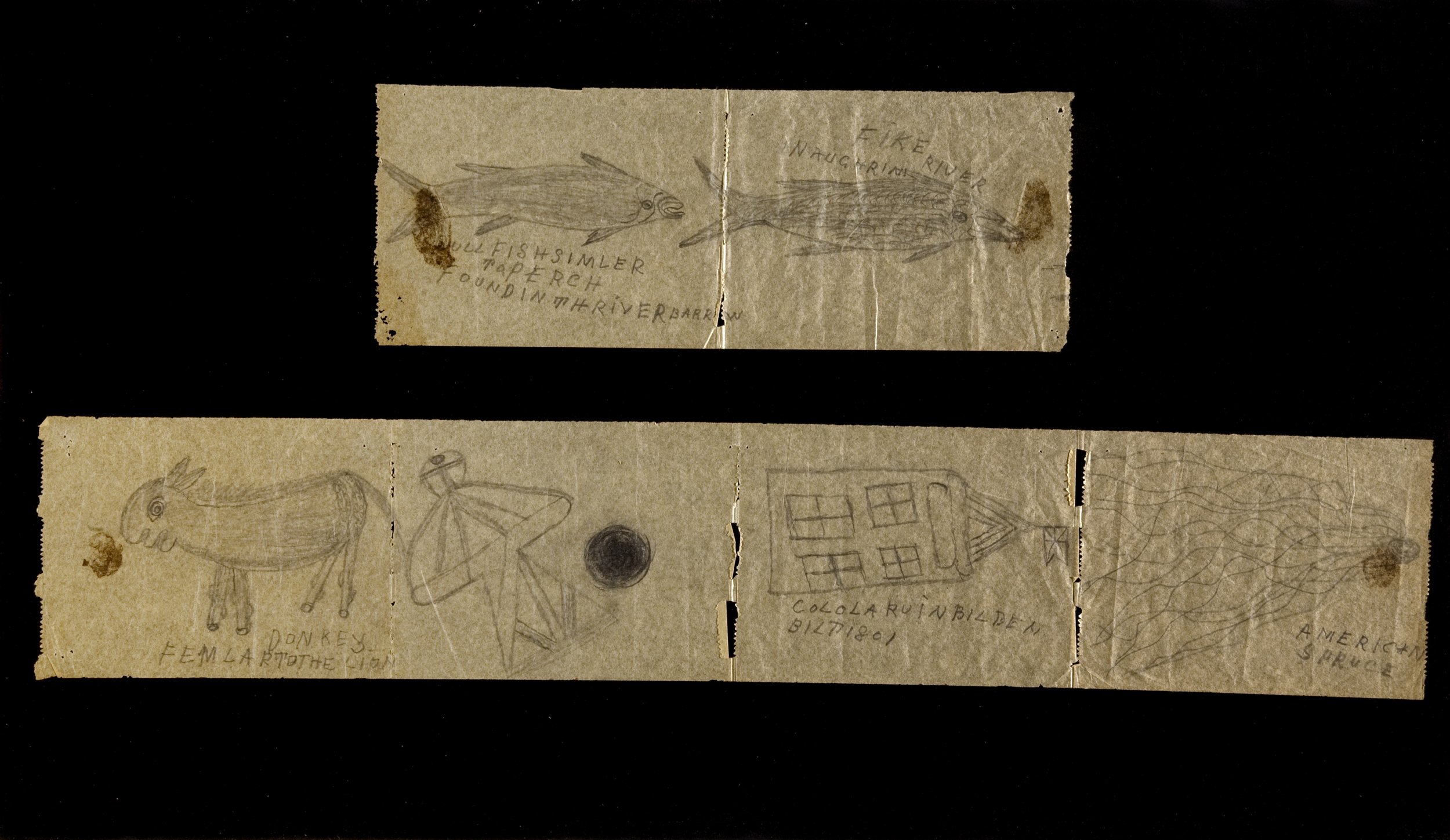

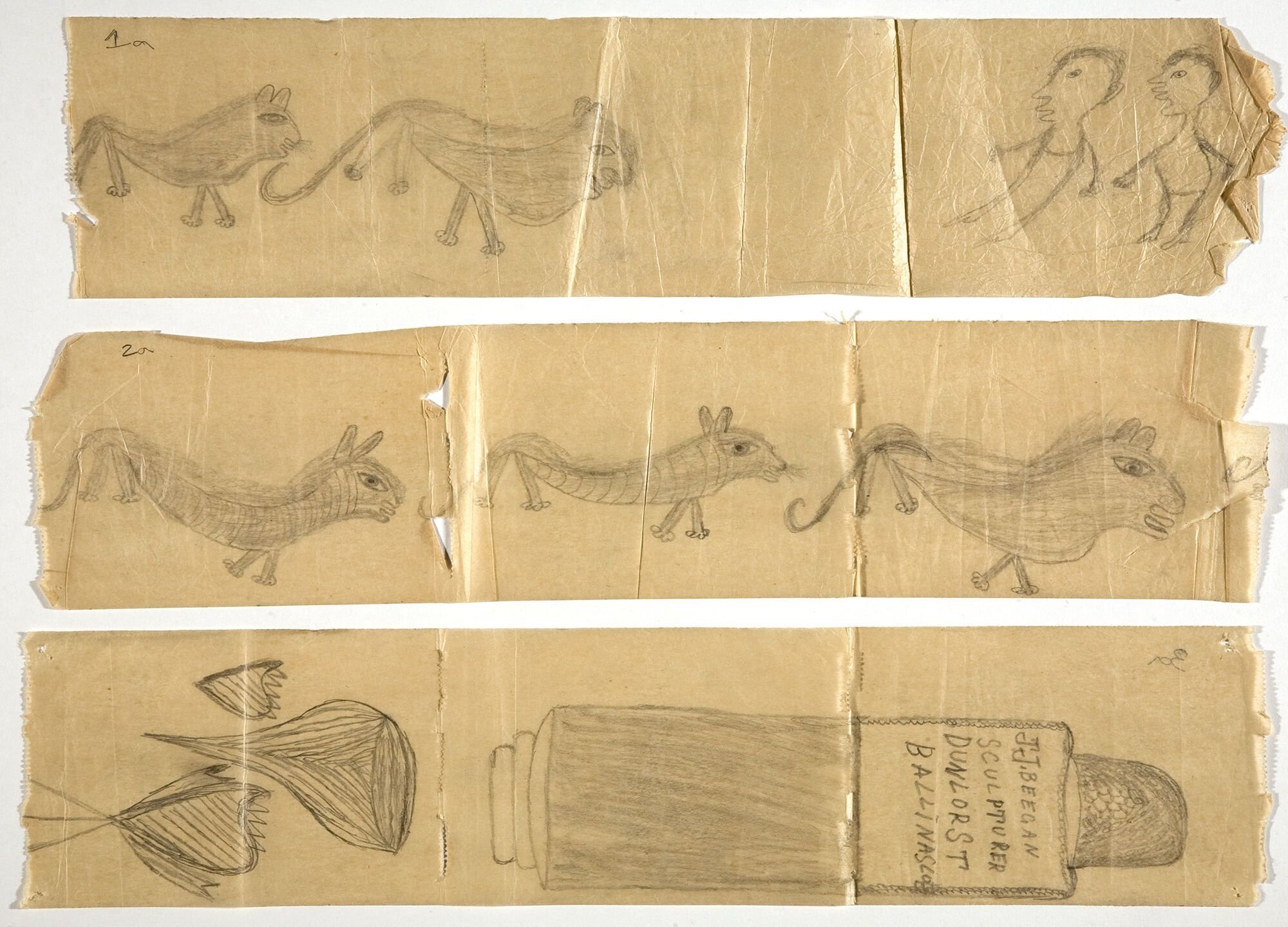

honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise is dedicated to the Ballinasloe-born artist and sculptor J.J. Beegan. In his drawings, he drew animals, such as birds, fish, lions and donkeys, as well as flowers and human figures in a sketch-like style, reminiscent of the drawings of the Irish artist Paul Roy (b.1967) FIG.3. At some point in the 1920s, he came to live in Netherne Hospital in Surrey, although there is no available information about how he arrived in England or why he was committed – nor indeed his dates of birth or death. Netherne Hospital was renowned for its art therapy programme, which was established by Edward Adamson in 1946. However, even before the arrival of Adamson, Beegan was already making art, using burnt matches to draw on toilet paper. These materials are extremely delicate, and it must have required great concentration and skill not to break the matchstick or tear the paper.

In one work FIG.4, Beegan drew two fish and named them ‘FIKE’ – most likely meaning pike – and ‘BULL FISH SHSIMLER TAPERCH’. Alongside these names, the fish were identified as being found in the ‘AUGHRIM RIVER’ and the ‘RIVER BARROW’. The Aughrim and Barrow rivers are both located in the south-east of Ireland, and the Aughrim is particularly renowned for fishing. In another charred matchstick work FIG.5, Beegan drew what appears to be three heart-shaped flowers, with a long rectangular object – perhaps a gravestone or medicine bootle – floating above. Two of the flowers have spiky petals, like crowns, with only the right flower retaining its stems. Text on the object reads ‘J.J. BEEGAN SCULPTERER DUNLOR ST BALLINASLOE’. Although it is impossible to confirm, it seems very likely that with this inscription Beegan is naming himself, identifying his profession as a sculptor and naming a relationship – and possibly home – in Ballinasloe. Beegan’s drawings were found damaged in a bathroom that was used for storage in Lambeth Hospital, London, where Adamson’s collection had been transferred following the closure of Netherne in 1996. An unknown number of his other works have been lost. Considering the fact that they were given the title of ‘graffiti’ even today, it is not difficult to imagine them simply being discarded.

Much of what is known know about Beegan comes from Clair Wills’s essay ‘Life pushed aside’, which was published in the London Review of Books in 2021. Because the records from Netherne Hospital are sealed, the details of Beegan’s life may be lost to what is a painfully common and violent institutional erasure. However, his work remains a testament to his life beyond the hospital walls, and a life lived between landscapes of medical incarceration. As Wills succinctly summarises:

J.J. Beegan was living in his own afterlife. The future was taken away from him and he chose not to live in the present. He didn’t draw the people around him on the ward or the views from the windows; he drew what he remembered from the life he had lived before. His pictures were his only means of communication, including perhaps with himself. On them he kept writing a name and address – the person he thought he should have been, or perhaps the person he wished he had been: J.J. Beegan, Sculpturer, Dunlo Hill, Ballinasloe.6

As part of TULCA, Beegan’s potent claim to selfhood was explored in a screening at Ballinasloe Library of Abandoned Goods (2014), a short essay film by Edward Lawrenson and Pia Borg that examines the art made by those living at Netherne, including Beegan. It was accompanied by a talk delivered by Wills, in which she described her search for Beegan and, crucially, discussed what happens when we cannot trace people. What, then, does the evidence amount to?

The site of St Brigid’s is examined in the audio and painting installation bless every foot that walks its portals through FIG.6 FIG.7by Aisling-Ór Ní Aodha (b.1996). The three paintings focus on architectural details of the hospital, creating a haunting intimacy with the site that still dominates the landscape. At the same time, the audio explores the hospital’s role within imperial rule in Ireland and the subsequent Free State policy of mass incarceration. In her film Echo’s Bones FIG.8 Sarah Browne (b.1981) examines sites of medical confinement. Named after the unpublished Samuel Beckett story of the same title, the film was made collaboratively with a group of young autistic people from North Dublin and takes place in the north country Dublin town of Portrane, which is home to St Ita’s Hospital. The project began with the group watching films made by neurodiverse artists, such as Mel Baggs’s In My Language (2007), Sharif Persaud’s The Mask (2019) and Jess Thom’s Me, My Mouth and I (2018), before collaborating on a work, including original music, which is for and by neurodiverse people. In many ways it is a simple portrait of a place and its young, local residents, yet rather than being a film about neurodiversity, it is a filmed through a neurodiverse lens. By using overtly cinematic techniques, such as blurred edges and close-ups, the film reflects some of the experiences of neurodiversity, challenging the assumption that a neurotypical view of a place is the one true way to see, hear and experience it. Fundamentally, it also highlights how neurodiverse behaviours are celebrated in the work of Beckett and art more widely, but are not given that same value in everyday life.

The film raises questions about how places such as St Ita’s imprint on the landscape and the people who live there. Yet it largely ignores the hospital itself, instead choosing to focus on the surrounding landscape FIG.9 thus reordering the power dynamics of how disabled people interact and engage with that site. The ultimate fate of these sites remains to be seen: some have been abandoned, while others have been turned into immigration detention centres, but most have unclear futures, continuing to stand and holding their weight upon a place. In the meantime, the neurodiverse view of a landscape presented in Echo’s Bones offers a way forwards in how we begin to process the history of these sites, and how to do so by centring anti-ableist methods.

Portrane is only a few miles north up the coast from Baldoyle, which was home to a residential hospital for disabled children, as well as the disability activist Martin Naughton (1954–2016). Naughton was born in the Galway gaeltacht (Irish-speaking) town of An Spidéal and moved to Baldoyle in October 1963, aged nine, with his sister Barbara due to lack of support services in his home town at the time. A companion publication for TULCA includes excerpts of Naughton’s forthcoming memoir Never Know Your Place.7 Titled Day One, it chronicles Naughton’s journey to Dublin through a series of interviews conducted by Joanna Marsden in the eighteen months before his death. It conveys the excitement that accompanies such journeys for a child – the modernity of train tunnels and double-decker buses – but also some of the hardships. Naughton was a monoglot Irish-speaker and the memoir relays his fear and confusion of living in a highly regimented environment and unable to find linguistic common ground. Naughton had a nuanced relationship with Balboyle, returning to work there as an adult, after a period of travel in the United States, where he came into contact with the Boston Center for Independent Living. On returning to Ireland, he established the first Centre for Independent Living in the country, which played a key role in the early disability rights movement, advocating for access to living support and ensuring that disabled people could live autonomously, without the risk or threat of institutionalisation. Naughton also campaigned for the closure of institutions.

Having to move to access healthcare and support services is a familiar concern for disabled people. In the film Cabbage FIG.10 by Holly Márie Parnell (b.1988) one encounters an intimate portrait of her family as they attempt to move home to Ireland from Canada. Their move to North America a decade earlier had been prompted by the severe cuts to disability services during austerity in Ireland. The film is the result of a collaboration with Parnell’s brother David, who writes using eye-tracking technology, and includes the recollections of their mother, June. She recounts the low expectations that medical professionals had for David during the diagnostic process, to which she responded: ‘I don’t know how you can measure the essence of being human’. Footage of verdant landscapes, the sea, of bird song and close-ups of David in the sun FIG.11, watching YouTube or speaking to June, lend the film a calm poignancy. These scenes are intertwined with images of June rifling through the vast piles of paperwork detailing doctors’ opinions, many of which are dismissive of David’s chances in life – as June explains, there is a sense of ‘just writing him off’. David asks questions throughout the film, such as ‘does my body surprise you? Does my body inspire you? Does my body scare you?’. In a later scene we see a new wave of digital paperwork being generated in order to secure David the services he needs to return home. June wears a necklace with a Claddagh ring hanging from it, a symbol that is synonymous with a neighbourhood in Galway City, but which has also come to represent a sense of Irishness and home for those living abroad.

Cabbage relates, with profound clarity, how much David and his family long to return home to Ireland, but also how many barriers they face, as well as the feeling that they have ‘had to leave Ireland twice’ because of the lack of support. In this sense, the film is an account of the displacement of disabled people and their families due to austerity. At the same time, it is also a tender account of access to intimacy: ‘that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else “gets” your access needs. The kind of eerie comfort that your disabled self feels with someone on a purely access level’.8David and June share an intimacy around what he needs and wants, on a fundamental, emotional level. Filling out a report detailing David’s care needs to service providers in Ireland, June remarks ‘it’s hard to get that all across in little bullet form’, listing one of his requirements as ‘being outside, even late in the night looking at stars’. It is this basic but vital need – human right, in fact – for dignity and freedom, to simply be outside and look at the stars, which Cabbage is about. It is a stridently anti-ableist account of the violence of bureaucracy and the agency of disabled people.

The video-essay Forgetting Is The Sun FIG.12 by Rouzbeh Shadpey (b.1992) engages with the entangled relationship of family, state, medicine, history and memory. It juxtaposes footage from the artist’s grandmother – who remains silent during a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), while counting a tespih (prayer beads) – with scenes from two films that challenge methods of remembering: The House is Black (1962) by the Iranian poet and film-maker Forugh Farrokhzad (1934–67) and Mémoire 14 (1967) by the Moroccan poet, film-maker and writer Ahmed Bouanani (1938–2011). It weaves together personal memory and collective history, recontextualising Farrokhzad’s and Bouanani’s defiance of state-sanctioned regimes of remembering through the lens of individual forgetting, and its resistance to the medical capture of the memory test. As a former practicing doctor, Shadpey has conducted the MoCA test many times in his career. By depicting the contingent relationship of health to the state, he questions the means by which memories are validated, and the role of the state in maintaining these institutional structures.

The film opens with scenes from The House is Black, which depict Bababaghi, one of two leper colonies in Iran, where the director spent twelve days in 1962. When asked how she gained the trust of those living in the colony, a crew member responded: ‘Forough lived, ate, sang, danced, slept, laughed and wept amongst them’. The institution of the leper colony acts as the ultimate site of medical exclusion and stigma, both practically and symbolically. Its occlusion from the state that created it, and from society more broadly, has led to an irreconcilability with its own identity that shrouds the institution even from itself. Shadpey highlights this by quoting a moment of simple humanity for institutionalised disabled people and the seemingly unimaginable act of human decency in Forough’s process. In sharing filmic space between a MoCA memory test and a leper colony, the film exposes the role of health and its treatment as a disguised agent in the formation of national memory, and by extension personal identifies. It positions medicine, often maligned as a secondary concern, within a system of power that shapes the makeup of the nation state and the myths it (re)tells about itself.

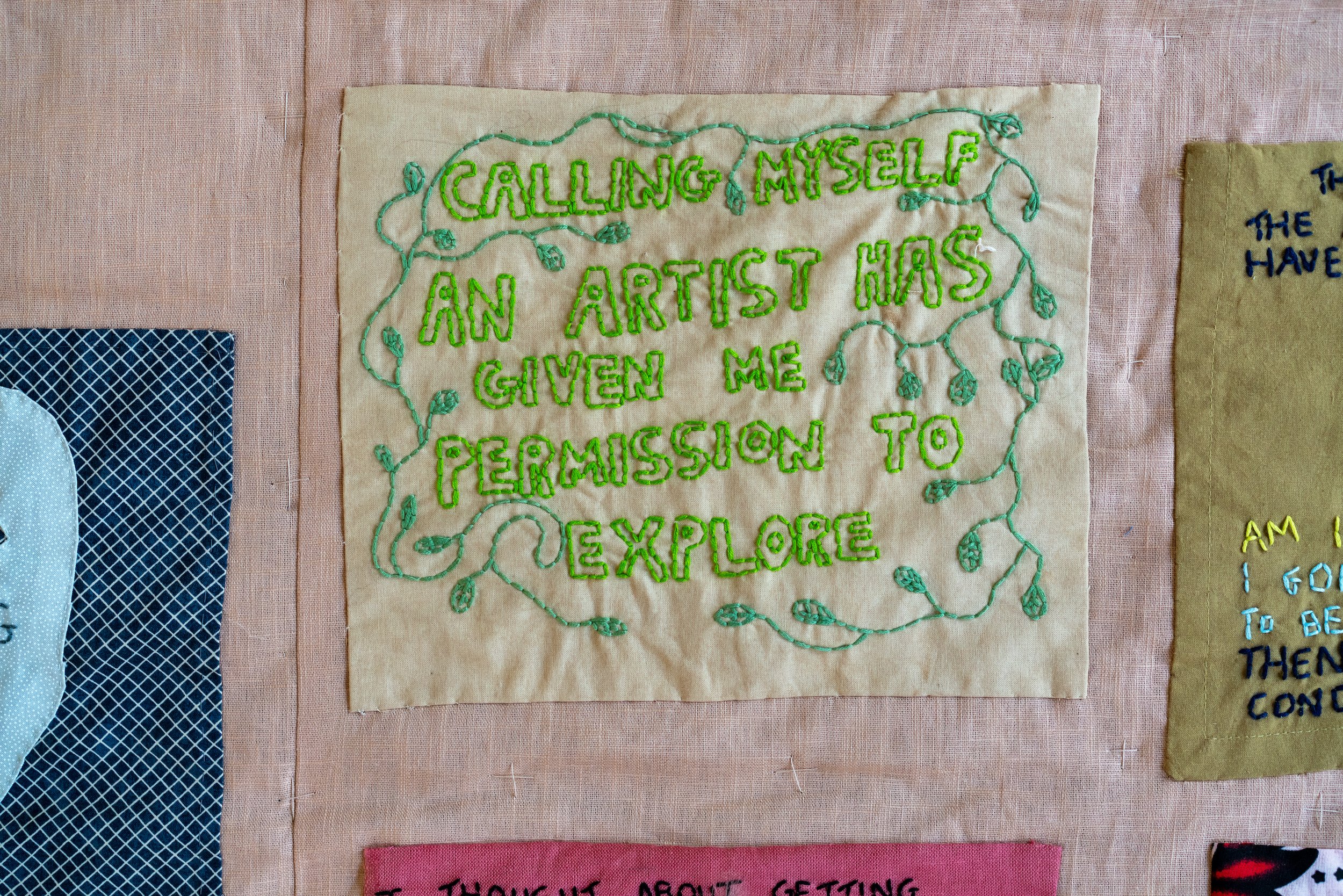

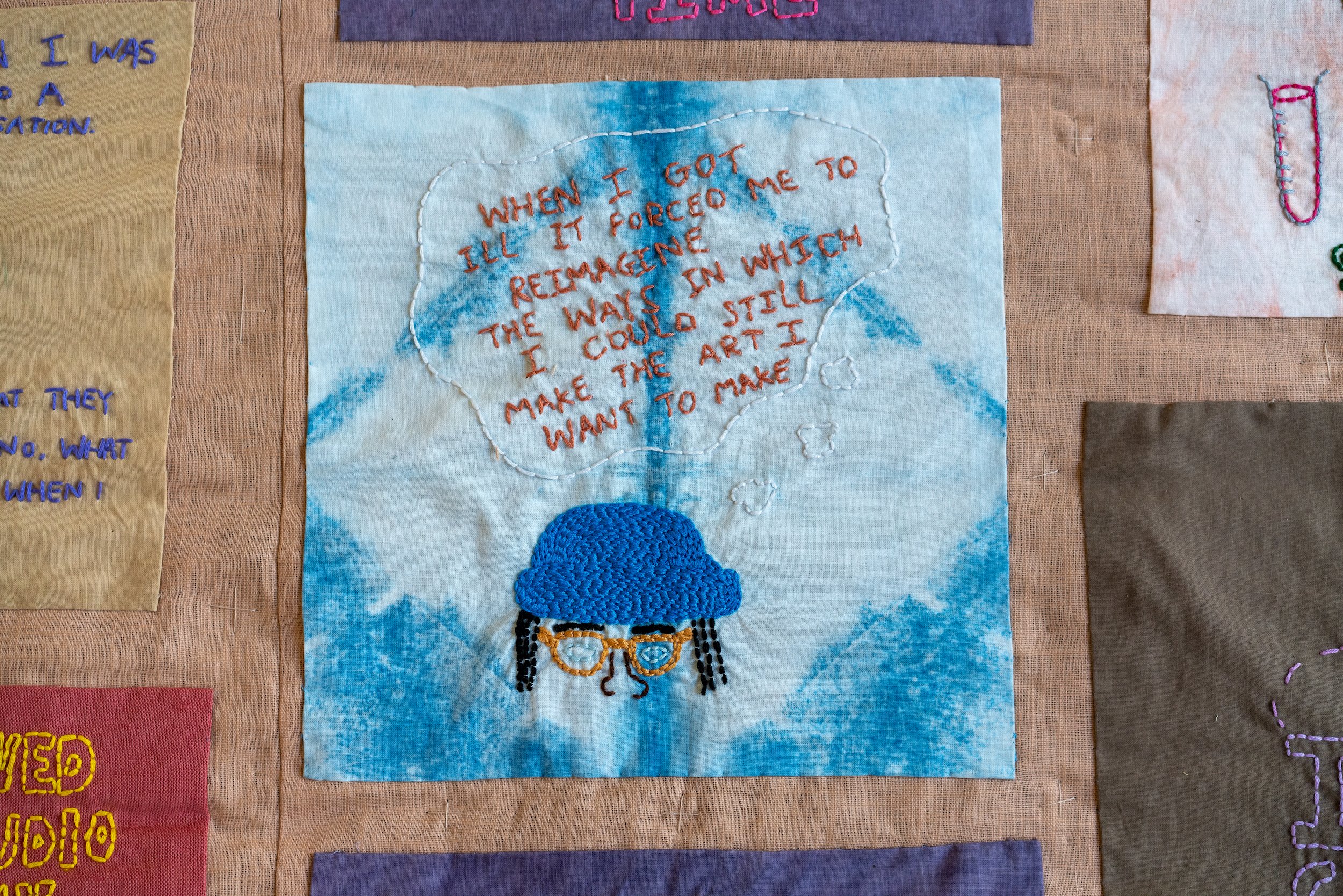

In the process of conducting research for the TULCA Festival, it became clear how few archives exist that contain first-hand accounts of disabled people, particularly institutionalised peoples and artists. Of those that do exist, many have been lost or sealed due to their status as medical records. In addressing this lack, the artist Jamila Prowse (b.1994) made Crip Quilt FIG.13, a large-scale, patchwork, textile quilt translating the individual and collective experience of disability. It includes contributions from the National Disability Art Collection and Archive, three new collated oral histories of disabled artists of colour and the artist’s own lived experience. Each square in the patchwork conveys a snapshot from the life of a disabled artist FIG.14. While making the quilt, Prowse found that the act of stitching helped to alleviate the symptoms of her disability, and her embroidered reflections took on a diaristic, confessional tone. Made on crip time – predominantly from bed – the quilt has been made intentionally heavy to reflect the use of weighted blankets in managing anxiety disorders and calming flare-ups and burnouts for neurodivergent people.9

Quilted sections of text read: ‘One of the biggest barriers is unrealistic expectations of time’, ‘I moved my studio into my home and I started to work again’ and ‘When I got ill it forced me to reimagine the ways in which I could still make that art I want to make’. Within the tradition of quilt-making, weaving the everyday lives of disabled artists into a physical object makes such realities visible and also creates material memories, sharing the possibility and strategies of crip making with future artists. In the context of the glaring lack of archival material, Prowse’s preservation of experience and knowledge is nothing short of a gift.

As part of the work of addressing the legacy of ableism in the West of Ireland, a core tenet of the TULCA Festival is a commitment to accessibility, reducing access barriers for disabled, sick, chronically ill, Mad or d/Deaf audiences to participate in the festival. For the 21st edition this included captioning all films and providing audio description tours, which were conducted by the education team. Many of the exhibited films have audio-described versions and there were transcripts provided for sound works. There were plenty of seats and spaces to rest, and the accompanying booklet featured access statements to support audiences with their visit.

As a disabled person who grew up in Galway, I carry an embodied sense of the ableism of this place and its violent legacy. This landscape is loved deeply: its rocky hills, its frigid waters and its sodden fields. It will always be home, and in that there is a responsibility to look beyond the romanticism of its beauty. In addressing this carceral legacy and the often brutal treatment by the state of disabled people, honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise is an act of solidarity with all incarcerated peoples and a means to broaden our abolitionist perspective. It is a call for us to fully account for the legacy of eugenic policies to address ableism as a central vehicle of the carceral system and to centre disability justice within abolition.10 This dedication is an attempt to name that violence. In doing so, in understanding how its sinews stretch and pull, we might begin to unravel it, and bring forth a future that centres disability justice and eradicates the carceral institution, wherever it may sink its claws.

Iarlaith Ní Fheorais is a curator and writer. She is currently the curator of the 21st edition of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts. As a writer she has written for Frieze, Burlington Contemporary, Viscose Journal, Girls Like Us, and has an art and access column with Visual Arts News Sheet. She regularly contributes to public programmes and lecture, including at Somerset House, London; KW Institute, Berlin; Konstfack University, Stockholm; and Arts and Disability Ireland. Committed to anti-ableism in the arts, she is working on a free online access toolkit for art workers, to be published in 2023.

1. ‘Ireland’s high committal rates which substantially outpaced those in England, Wales and Scotland and by the 1950s resulted in Ireland having the highest rate of psychiatric bed availability internationally’, B. Kelly: Hearing Voices: The History of Psychiatry in Ireland, Newbridge 2016, p.2.

2. ‘[The asylums] functioned as vast, unwieldy social welfare system for patients and possibly some staff [so much so that] in 1907, 30 percent of admissions [for one Dublin asylum] came directly from workhouses […] which leads to the conclusion that the Irish asylum system was a social creation as much as it was a medical one’, ibid., p.2.

3. J. Wilde: Ancient Cures, Charms and Usages of Ireland, London 1890, p.34, quoted in Kelly, op. cit. (note 1), p.28.

4. According to Talia A. Lewis’s working definition, ableism is a ‘system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. This systemic oppression leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth or living place, ‘health/wellness’, and/or their ability to satisfactory re/produce, ‘excel’ and ‘behave. You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism’, T.A. Lewis: ‘Working definition of ableism’, talialewis.com (1st January 2022), available at www.talilalewis.com/blog/working-definition-of-ableism-january-2022-update, accessed 20th November 2023.

5. In 2019 Recess, New York, commissioned an accessibility guide geared toward small-scale arts non-profits and the potentially expansive publics these organisations serve. As set out in the introduction, disability justice ‘is the second wave of the disability rights movement, transforming it from a single issue approach to an intersectional, multisystemic way of looking at the world. Within this framework, disability is defined as an economic, cultural, and/or social exclusion based on a physical, psychological, sensory, or cognitive difference. Disability Justice movements understand disability to be unevenly distributed, primarily affecting black and indigenous communities, queer and trans communities, and low income communities. Disability is structurally reinforced by ableism, a system rooted in the supremacy of non-disabled people and the disenfranchisement of disabled people through the denial of access’, C. Lazard: Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice, New York 2019, available at promiseandpractice.art, accessed 24th October 2023.

6. C. Wills: ‘Life pushed aside’, London Review of Books 43, no.22 (18th November 2021), available at www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n22/clair-wills/life-pushed-aside, accessed 20th November 2023.

7. J. Marsden: ‘Day one’, in I. Ní Fheorais, ed.: exh. cat. honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, Galway (various venues) 2023, pp.18–23.

8. M. Mingus: ‘Access intimacy: the missing link’, leavingevidence.wordpress.com (5th May 2011), available at leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link, accessed 21st November 2023.

9. See A. Kafer: Feminist, Queer, Crip, Bloomington 2013, esp. p.27.

10. ‘Disabled/neurodivergent people comprise just 26% of the united states population but represent up to half of the people killed by police, over 50% of the incarcerated adult prison population, up to 85% of the incarcerated youth population. Knowing this, we are left no choice but to view carcerality much more broadly, through a disability justice lens. If we fail to fill this gap in our collective consciousness, ableism will continue to be used as an excuse for inflicting violence upon marginalised people under the guise of care, treatment, and rehabilitation’, T.A. Lewis: ‘Disability justice is an essential part of abolishing police and prisons’, Medium (7th October 2020), available at level.medium.com/disability-justice-is-an-essential-part-of-abolishing-police-and-prisons-2b4a019b5730, accessed 20th November 2023.