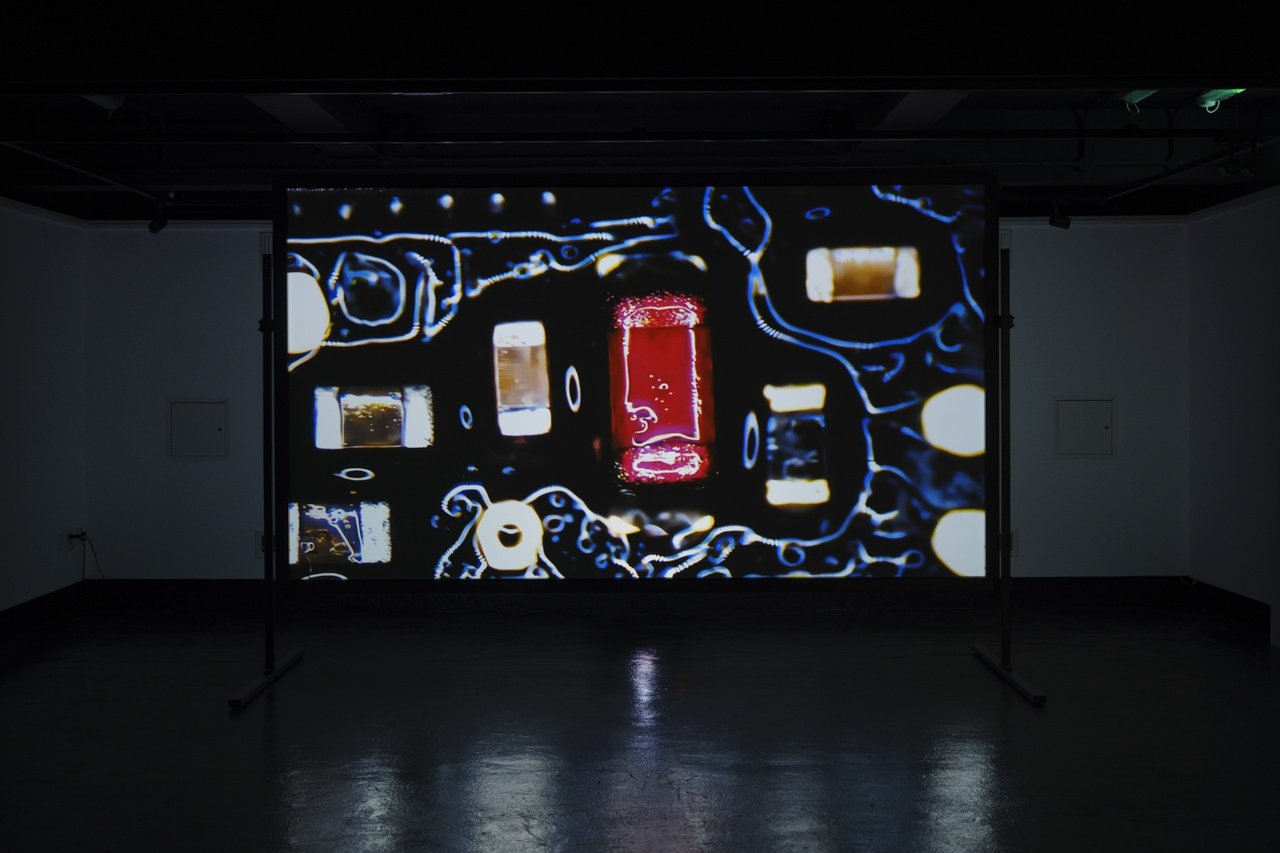

Jenny Brady, “Music for Solo Performer,” 2022, in “honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise,” TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, 2023

The Paucity of Care | Chris Hayes

Over the course of the last century, no nation in the world institutionalized a greater proportion of its population than Ireland did. A significant portion were confined in mental institutions established by the British. The material remnants of this colonial history still leave their mark on the landscape of western Ireland. Highlighting Ireland’s west as a terrain of medical infrastructure and control, the recent TULCA Festival of Visual Arts in Galway prompted artists to examine the region’s relationship with medicine. Not surprisingly, the exhibited works center around on themes of accessibility, cure, and care. But, as Chris Hayes describes, this focus extends beyond the artworks to encompass considerations in exhibition design: through a collaboration with the advocacy group Arts & Disability Ireland, tools for accessibility, often viewed as afterthoughts to aesthetic and curatorial decisions, productively integrate into TULCA’s structure.

Every year, TULCA, an annual arts festival in Galway on the west coast of Ireland, invites a new curator to shape its program. The constant entry and exit of a central figure becomes a familiar foundation to the festival’s surrounding discourse, inviting comparisons between the latest edition and previous years. For Iarlaith Ní Fheorais, curator of the 21st edition, entitled “honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise,” a partnership with advocacy group Arts & Disability Ireland represents a practical choice and also a deeper statement of intent that reverberates through the many video installations, audio works, paintings, sculptures, quilts, and performances. The focus on accessibility was notable in multiple small and large ways: captioning for video installations; a dedicated masked launch event; audio described tours during the course of the program. But most strikingly, the inherent accessibility in the program is connected with a deeper conversation around disability and bodily difference.

Take Jenny Brady’s Music for Solo Performer (2022), for example. The single-channel video installation is a meditation on varied notions of the body told through the idiosyncratic relationship the artist’s mother had with the American singer and comedian Jerry Lewis. Blending pop culture, biography, and the history of technology, the film shifts fluidly across varied notions of embodiment and the body: the camera pans across close-up shots of computer motherboards, microchips, and a digital rendering of the contours of a brain, visually suggesting each is a comparable system; we hear about Lewis’s philanthropic support of disabled children; we see footage of a soldier with a disfigured face that has been “fixed” with AI, so the visuals on screen glitch and flicker, blurring the line between skin and mask, background and foreground, history and contemporary reimagining. The montage of scenes revolves around illness, injury, and attempts to use technology to resolve the inescapability of the body’s fragility.

I first saw this film with the audio-visual captioning. The viewing experience appeared to be modified slightly, perhaps slowed down in specific scenes, although I wasn’t certain. The interplay between archival images from the history of medical institutions, TV reels of science experiments on the intersection of the body and machines, and Lewis’s high-flying energetic presence is held together by the artist’s voiceover. It’s only in the second viewing, without the audio-visual captioning, that making a distinction between the “original” and the “accessible” version became possible, despite how slight and partial it was. At one level, the content of Brady’s work is a funny and heartfelt reflection on the body, ageing, and disability. But the interplay between voice, text, and image on screen is clearly shaped and informed by the dynamics of audio-visual captioning itself, both as an artistic gesture and perhaps a politics, too.

“honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise,” TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, 2023

“Honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise” has been contextualized within the medical histories of Ireland, and more specifically, of the surrounding rural areas of Galway. “To go to Ballinasloe,” writes Ní Fheorais in her curatorial text, “was a once familiar turn of phrase for many in the West of Ireland.” [1] The euphemism referred to the mental health facility by the town which is close to Galway city, but the need for indirect speech and implication gestures toward a wider culture of stigma and silencing. Ballinasloe is significant in many ways; notably it was one of the first mental health institutions with an arts therapy program in the world, but it is also notable how unremarkable, how ordinary, it was within the cultural and political landscape of a country where institutionalization was a common fact for many. In the 1950s, Ireland had one of the highest rates of institutionalization in the world – a much higher rate than comparable statistics found in the USA or Soviet Union. The practice of artist J. J. Beegan is foregrounded in the festival’s curatorial text and related material, although none of his work is present in the exhibitions. Beegan was an artist and sculptor who was a longtime resident of a mental health facility in Surrey, England, during the 1940s, but he claimed repeatedly to be from Ballinasloe and often made references to it in his drawings made from burnt matches and toilet paper. It’s not certain if this is true. But by referencing the life of Beegan as a symbol for others who have been denied agency, and by contextualizing this discussion within the troubled legacy of institutionalization in Ireland and elsewhere, the festival draws a link between the politics of the body and the production of art.

Beyond a conceptual framing, bodily difference can pose practical problems. As Bridget O’Gorman was physically unable to make her sculptural works, she collaborated with an assistant, Sandra McAlister, to create works that bear witness to their own construction. While it’s not uncommon for high profile, commercially successful artists to rely on a team of assistants to scale up their production, the context of need shifts how we can understand O’Gorman’s choice, while also bringing in notions of collaboration, exchange, and change – all artists rely on a support network, whether that’s family, friends, peers, and other more professional services, yet disability makes this more explicit and urgent. In the gallery, a range of delicate, slight sculptural forms sit, hang, and lean. Slings and hoists hold the work, and are also part of it. Other medicalized material accompanies the fragile, beautiful jesmonite forms cast from assistive devices. The installation occupies the space as if it was a trace of something else or another activity. Reflecting on the process behind the works, the artist wrote: “You had the notion of casting limbs, yes you would call them limbs because for one thing, they posit a gesture. What you mean is that they speak to vulnerability, a vulnerability to be rehearsed or enacted against the hostile architecture of the gallery.” [2]

Just across the street in a modest exhibition space, the artist duo Roberta Murray and Orla Meagher, members of the collective Bog Cottage, created a space in the style of a faery fort for festival visitors to rest and recharge. Rooted in Irish folklore, these forts are typically modest creations: the ruins of circular stone buildings from early Christian Ireland, they are often little more than a dirt mound, piles of stones, and a clump of trees. For their installation, Faery Fort(2023), Bog Cottage created a calming space with an ambient soundtrack, embroidered fabrics hung from the ceiling, and seating. It was created to be welcoming to neurodivergent people, while also providing a place of rest, and it also hosted an immersive meditative workshop during the course of the festival. Beyond the installation’s functional and practical role, its details, such as the images embroidered into the fabrics and an accompanying poem by Ainslie Templeton, embody something of a devilish spirit akin to those of the faeries themselves. As Templeton’s poem states: “The line between a blessing & curse is vexed.”

Bog Cottage, “Faery Fort,” 2023, in “honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise,” TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, 2023

Where O’Gorman confronts the process and form of her work through a lens of the body and its fragility, Bog Cottage creates a space that is conscious of the visitor’s own needs, particularly the strain of navigating a city-wide series of exhibitions and events. Other works extend the conversation to landscape and community. Sean Burns’s film Dorothy Towers (2022) looks at a social housing development in Birmingham, which took on a particular significance for the gay community; it discusses HIV stigma and far-right violence, but also tender moments of identity, self discovery, and care. Both Sarah Browne’s film Echo’s Bones (2022), a collaborative project with young autistic people that makes reference to an unpublished Samuel Beckett story, and Rouzbeh Shadpey’s Forgetting Is the Sun (2023), a video essay that draws links between a dementia test and the legacy of Iranian resistance, are structured around the experiences of autism and dementia. And Holly Márie Parnell’s Cabbage (2023) is a filmic portrait of her brother David’s experience with austerity-driven cuts to disability services, telling a story of bureaucratic hurdles that is tender, heartbreaking and, at times, fiendishly funny. Across a myriad of works, disability and illness are the starting points for an artistic engagement with visual language, particularly film; this engagement is the basis of a critique of capital and institutionalism, and has an impact on the relationships the artists conceive between themselves, their subjects, and their audiences.

As the vocabulary of “care,” “accessibility,” and “representation” is increasingly adopted by galleries and museums across the art world, while efforts toward inclusion are too often partial or absent, it feels all the more important to not forget about how bodies have been medicalized and how institutions have perpetrated violence, and to think more precisely about what this remembering might entail. With this history in mind, the ways in which the artists at TULCA are exploring an expanded aesthetic around accessibility, the relationship between text, image, audio, and the audience, and notions of productivity and process takes on another level of significance that resonates beyond the festival.

TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, Galway, November 3–19, 2023

Chris Hayes is an Irish writer based in London. His work has been published by Art Monthly, ArtReview, Burlington Contemporary, Frieze, Tribune, and The White Review, amongst many others.

Image credit: Courtesy TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, photo Ros Kavanagh

NOTES

[1]Iarlaith Ní Fheorais, “From Ballinasloe to Netherne: the Drawings of J. J. Beegan,” in honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise, exh. cat., ed. Iarlaith Ní Fheorais (Galway: TULCA Publishing, 2023), 4.

[2]Bridget O’Gorman, “Hoist (Act I),” in Support | Work, commissioned by TULCA Festival of Visual Arts. Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c799b17755be23799b82d54/t/65442e576f101f2c44250b79/1698967127644/Support+_+Work_Final_Text.pdf.

Feb. 23, 2024