On The Medical Condition Of A Landscape | Theresa Zwerschke

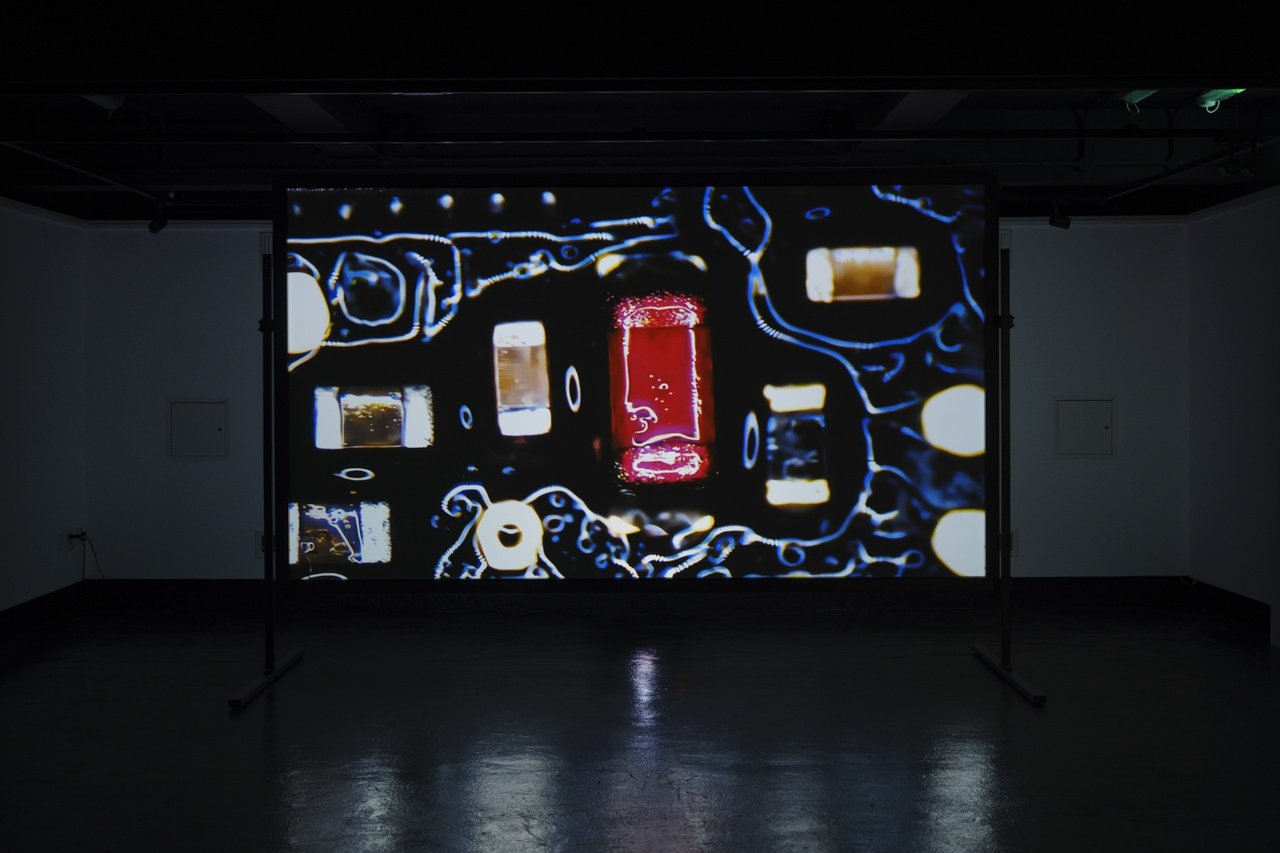

Notes on honey, milk & salt in a seashell before sunrise - the 21st edition of TULCA Festival in Galway.

What else is a landscape than a “backdrop for the experience of seeing”? [1]

I’m sitting on the train to Galway, to attend the opening of the 21st edition of TULCA, an art festival in the West of Ireland. As my gaze slides over green fields divided by neatly stacked stone walls, some are occasionally inhabited by herds of sheep, confirming my presumptuous, romanticized idea of pastoral Ireland. I think of Lucy Lippard's definition of landscape as an activity, “a way of seeing the world and imagining our relationship to nature.” [2] Landscape as an actively produced image, emerging from an external perspective that gets mediated through experiences, knowledge, ideologies, and the historical narrative written into it.

The exhibition honey, milk & salt in a seashell before sunrise addresses a landscape of medical incarceration. One that is deeply embedded in Ireland’s history of mental health institutions and inseparable from its colonial past. Tracing back to the 1830s, a time when Ireland was ruled by England, the institutions hold evidence of the aftermath of this period of domination and the implications it left on the medical complex. Consequences of the British occupation, such as oppression, poverty, or migration of family members played a role in the incarceration of many in those hospitals. The medical condition of the Irish landscape forms the backdrop for our experience of seeing. Questions around access, health, home, and belonging are posed and contested in the context of the festival. Spread over various locations in and around Galway, a harbor town of 83.500 in the West of the country, TULCA presented a festival including exhibitions, screenings, talks, readings, and a mediation program in November 2023.

“In the 1950s, Ireland imprisoned more of its population than any other state at the time, the largest cohort of which were living in mental health institutions,“ [3] writes the curator Iarlaith Ní Fheorais in the accompanying publication. Committed for various reasons and labeled “mentally ill” or “socially dysfunctional”, inmates of these hospitals, which were located in many Irish towns were segregated from the local economy in sites that were, first and foremost, centers of control.

The history of medical incarceration inscribes itself into the landscape of West Ireland, with mental hospitals, built in an “X” shape with a central watchtower, as is the case of the St. Bridgit Hospital in Ballinasloe in Galway. In its resemblance to prison architecture, the building presents itself as an almost perfect example of Michel Foucault’s panopticon: the surveilling architecture of the disciplinary society, which inevitably prompts understanding of the history of mental health institutions as being interconnected with the prison industrial complex.

The Black Panther Party continuously addressed this connection in the US American context in the 1960s and 1970s, challenging the medical and legal abuse in both structures, but also the “racialized norms of able-mindedness, which constructed appropriate behavior, mental states, emotions, and reactions based on white male middle-class norms,” [4] as Sami Schalk writes in TULCA’s publication. In light of the Panthers’ abolitionist activism, it seems crucial to understand the structural workings of power in the history of medical incarceration through a confrontation with its intersectional layers of gender, class, and race.