On The Medical Condition Of A Landscape | Theresa Zwerschke

Notes on honey, milk & salt in a seashell before sunrise - the 21st edition of TULCA Festival in Galway.

What else is a landscape than a “backdrop for the experience of seeing”? [1]

I’m sitting on the train to Galway, to attend the opening of the 21st edition of TULCA, an art festival in the West of Ireland. As my gaze slides over green fields divided by neatly stacked stone walls, some are occasionally inhabited by herds of sheep, confirming my presumptuous, romanticized idea of pastoral Ireland. I think of Lucy Lippard's definition of landscape as an activity, “a way of seeing the world and imagining our relationship to nature.” [2] Landscape as an actively produced image, emerging from an external perspective that gets mediated through experiences, knowledge, ideologies, and the historical narrative written into it.

The exhibition honey, milk & salt in a seashell before sunrise addresses a landscape of medical incarceration. One that is deeply embedded in Ireland’s history of mental health institutions and inseparable from its colonial past. Tracing back to the 1830s, a time when Ireland was ruled by England, the institutions hold evidence of the aftermath of this period of domination and the implications it left on the medical complex. Consequences of the British occupation, such as oppression, poverty, or migration of family members played a role in the incarceration of many in those hospitals. The medical condition of the Irish landscape forms the backdrop for our experience of seeing. Questions around access, health, home, and belonging are posed and contested in the context of the festival. Spread over various locations in and around Galway, a harbor town of 83.500 in the West of the country, TULCA presented a festival including exhibitions, screenings, talks, readings, and a mediation program in November 2023.

“In the 1950s, Ireland imprisoned more of its population than any other state at the time, the largest cohort of which were living in mental health institutions,“ [3] writes the curator Iarlaith Ní Fheorais in the accompanying publication. Committed for various reasons and labeled “mentally ill” or “socially dysfunctional”, inmates of these hospitals, which were located in many Irish towns were segregated from the local economy in sites that were, first and foremost, centers of control.

The history of medical incarceration inscribes itself into the landscape of West Ireland, with mental hospitals, built in an “X” shape with a central watchtower, as is the case of the St. Bridgit Hospital in Ballinasloe in Galway. In its resemblance to prison architecture, the building presents itself as an almost perfect example of Michel Foucault’s panopticon: the surveilling architecture of the disciplinary society, which inevitably prompts understanding of the history of mental health institutions as being interconnected with the prison industrial complex.

The Black Panther Party continuously addressed this connection in the US American context in the 1960s and 1970s, challenging the medical and legal abuse in both structures, but also the “racialized norms of able-mindedness, which constructed appropriate behavior, mental states, emotions, and reactions based on white male middle-class norms,” [4] as Sami Schalk writes in TULCA’s publication. In light of the Panthers’ abolitionist activism, it seems crucial to understand the structural workings of power in the history of medical incarceration through a confrontation with its intersectional layers of gender, class, and race.

fig. 1

These controlling and regulating functions of mental health institutions are explored in Aisling-Oi Ní Aodha’s work bless every foot that walks its portal through (2023), which consists of collages and an accompanying audio essay. Depicting architectural drawings of St. Brigid's Hospital, reminiscent of classic landscape paintings, the collages break through their supporting structures; these include little wooden bricks, strings, and embroideries, which visiblize the structure of the work itself, as well as the constructed-ness of the system that produced St. Bridgit’s architecture. In contrast to the oral cultural tradition, painting was a medium imposed by the British, says the artist. Visuality, the sense that is connected most with measuring, categorizing, and control is imposed by the colonizer. Appropriating and disrupting a traditional way of representation, for Ní Aodha, is also a way of interfering with the colonizer's tools.

Repurposing tools of display and presentation is not only seen in multiple works within the show but also in TULCA’s exhibition design. Access tools, which are often regarded as merely functional and in opposition to aesthetic, curatorial, and artistic decisions, seem to merge effortlessly into the exhibition architecture and contest ableist display standards. Frames are hung 110 cm from the ground, which orients to the viewing height of someone sitting in a wheelchair, creating a new norm of seeing in the show. Audio descriptions of video works become part of the formal language of the films. In Holly Marie Parnell’s Cabbage (2023), made in collaboration with her brother David, whose communication device - involving an eye movement tracing technology - gives the film its structure. By following David and their mother preparing for relocation back to Ireland (which they had to leave due to changes in disability services), the work documents the family’s relationship, and beautifully speaks of the wholeness of a human life beyond medical categorizations and care schedules. In the film, as their mother goes through boxes of old medical records detailing the clinical violence of fitting the essence of a human being into scales, the narrating audio carries the viewer into David’s reality.

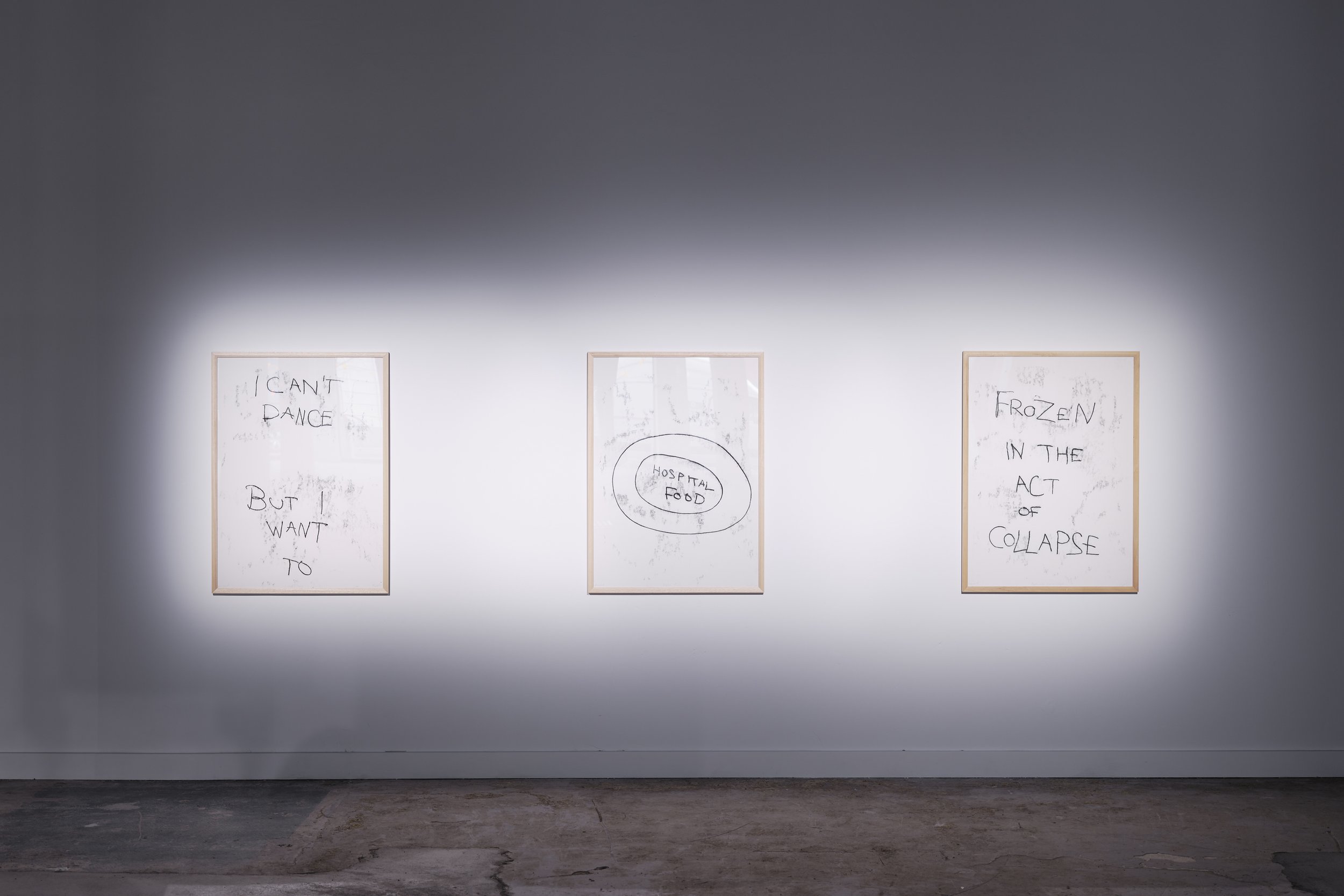

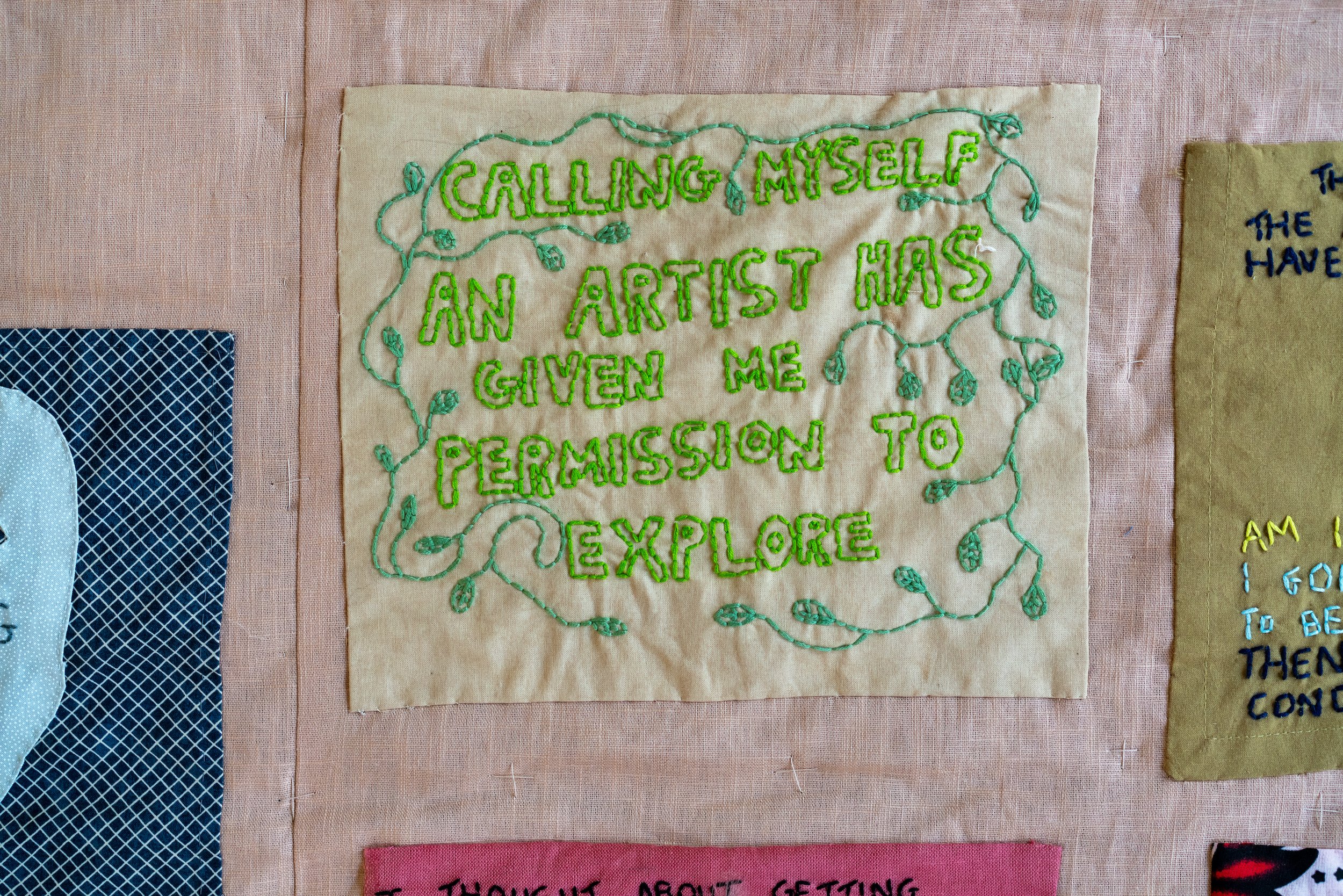

fig. 2

TULCA’s narratives do not remain in an observing position, but instead approach the medical landscape through lived experience. “A lived-in landscape becomes a place, which implies intimacy.” [5] This intimacy Lippard mentions is reflected in the booklet Access Intimacy [6] the exhibition offers, as well as in the language of those, who don’t enjoy the luxury of regarding the medical complex as a landscape; those for whom it conditions their experience of place. Bridget O’Gorman’s fragile installation, Support I Work (2023), was produced in close collaboration with her support worker. The hanging elements, made with medical support materials, both hold and fracture the sculptures, they document a translation of ideas into material, and thereby speak of the intimacy of their shared production.

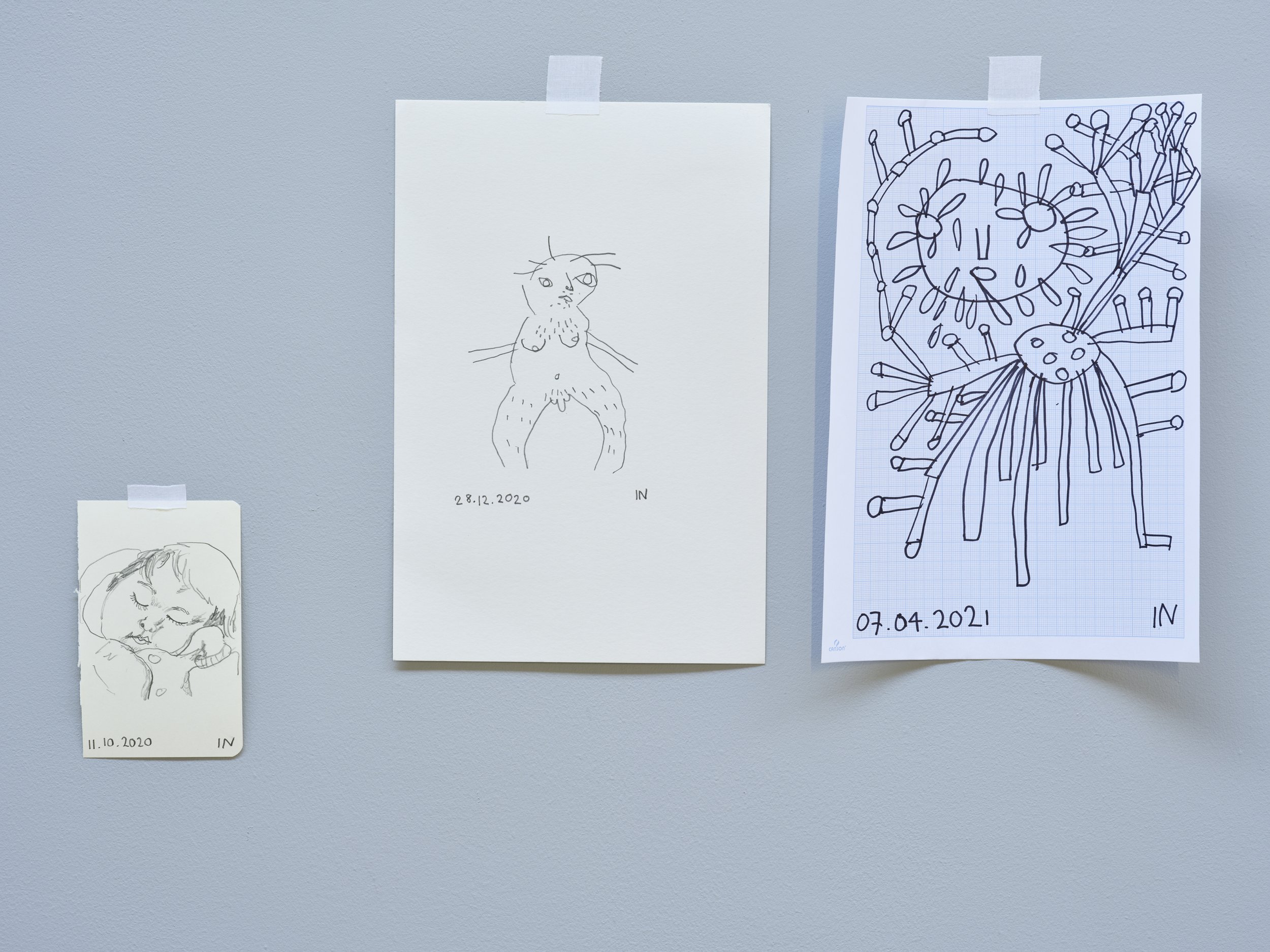

fig. 3

In Anna Roberts-Gevalt’s work Ridgewood Sick Center (2023), featuring a billboard in the University Hospital of Galway, I find drawings of a mountain landscape built from the artist's bed sheets. Between references to “sick ancestors” the billboard invites visitors to an audio tour and a radio broadcast from the hospital, for which patients can request songs as wishes via their phones. Passing patients, nurses, and visitors while walking through the labyrinth of aisles not only puts the hospital itself on display but also makes everyone in the hospital a potential festival participant.

fig. 4

Sean Burns’ film Dorothy Towers (2023) sensitively records the lived experience of inhabitants of two residential blocks in Birmingham that were built in 1971, and which has been a long-time home for the LGBTQ+ community. Long-shot architectural sequences are merged with interviews and archival documentation of a generation of inhabitants, celebrating their togetherness amidst the horrors of the AIDS pandemic. His film - partly shot on 60mm - is shown at the 126 Gallery, the only artist-run space in Galway. The nostalgia connects with my own melancholy thoughts about the role of economic changes in erasing self-organized art and subculture. Walking from one festival location to the other, through cute little streets with stylish cafés and local shops, I can’t help but be struck by the contrast of the homeliness, with which contemporary Galway presents itself and the hauntings of its past.

Leila Hekmat’s film, Symptom Recital: Music for Wild Angels (2023), which premiered in the Pàlàs Cinema on the fourth of November, troubles the landscape/place distinction using a sassy theatrical performance centered on the “Hospital Hekmat”, in which “the patients and staff share a hysterical language.” [7] Inhabitants of the Hospital share their stories and desires while shifting in and out of roles and chants, mocking and teasing each other (and their audience) and throwing rigid parameters of care, sexuality, and well-being into question. Acknowledging the fluidity and social determination of the protagonist’s positions on a scale between binary poles of sickness and health ties Hekmat’s film to the core demands of The Mental Patients Union, founded by both patients and hospital workers within the antipsychiatry movement of the 1970s. In their connection to Marxist ideology, the MPU demanded a questioning of the economic forces at play in categorizations of “sickness” and “health”, placing mental illness “in the context of capitalism, to disentangle it from the biological and psychoanalytic theories that defined it,” [8] as Roisin Agnew elaborates.

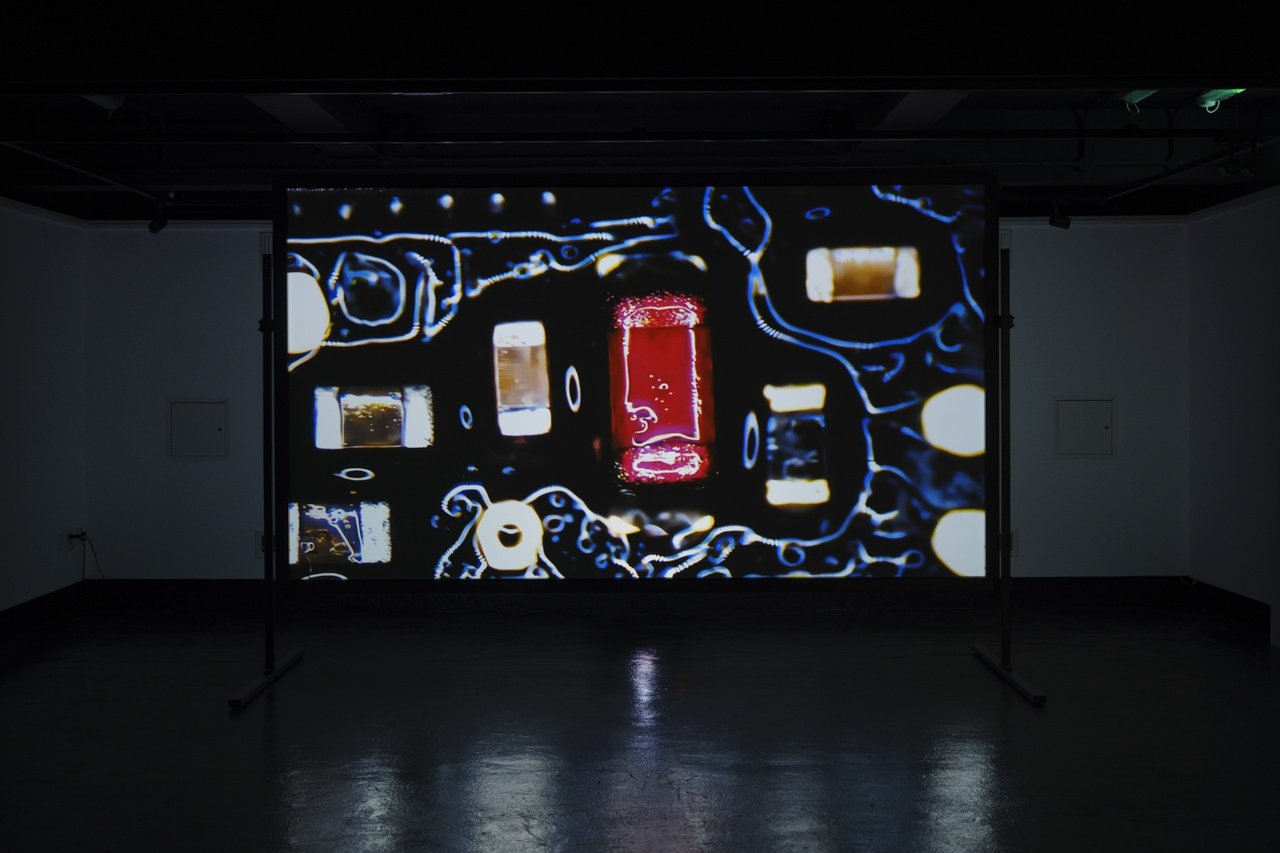

fig. 5

The hegemonic indoctrination of collective remembrance is faced with the position of forgetting as a physical condition in Rouzbeh Shadpey’s video essay Forgetting is the Sun (2023). The film intercuts sequences of his grandmother’s hands repeating answers to a memory test imposed by an invisible narrator with archival footage of other video essays by Forough Farrokhzad and Ahmed Bouanani. Considering individual forgetting as both an act of resistance against biopolitical forces and a moment for achieving composure, the narrator states: “Through the lens of her camera, Fourough afforded those deep lepers the gift of the impossible - that is: the possibility to forget.“ [9]

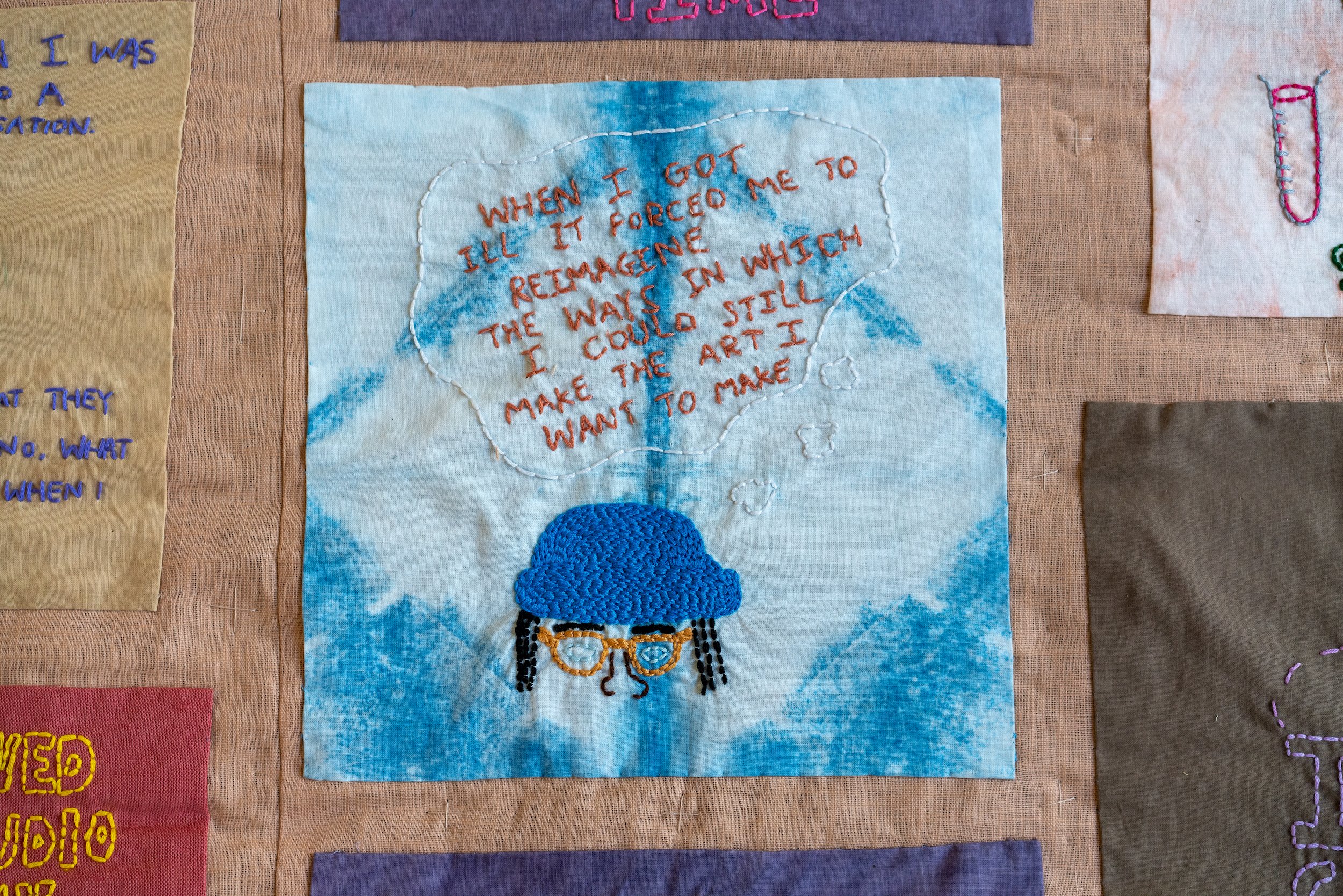

Philipp Gufler’s Memorial Quilts (2022) entangle the relationships between individual and collective memory by asking who are the ones that are remembered. The quilts offer a glimpse into Philipp Gufler's extensive, ongoing research into historically underrepresented queer personas upon which he works closely together with Forum Queeres Archiv, München. Depicting stylized, collaged portraits of queer German ancestors - the pop star Lana Kaiser, the painter Lorenza Böttger, the writer Daniel Paul Schreber, and the doctor, sexologist, and writer Charlotte Wolff - these quilts make those portrayed symbols for the celebration of queer life, and the work pushes against their systemic historical erasure.

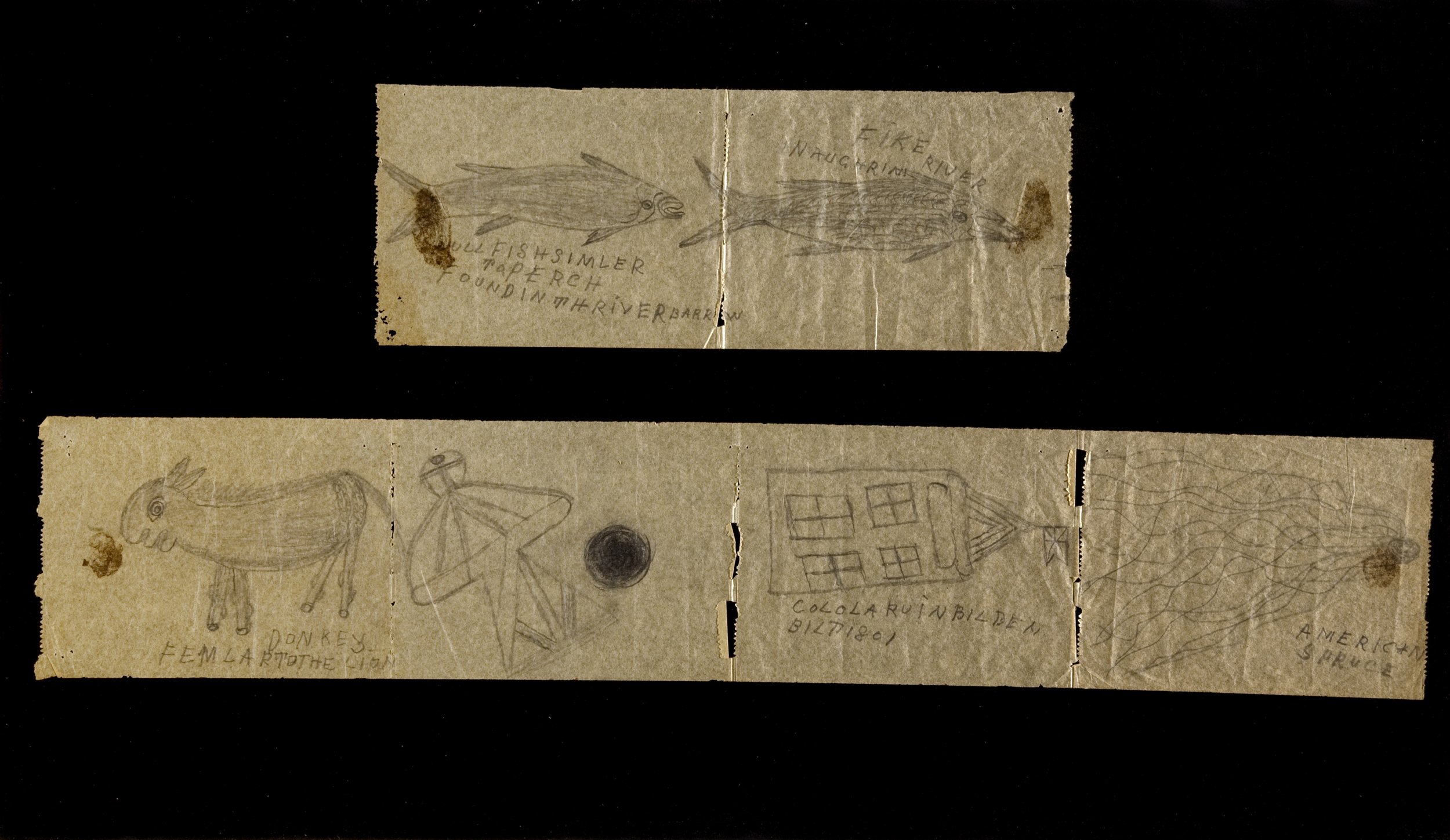

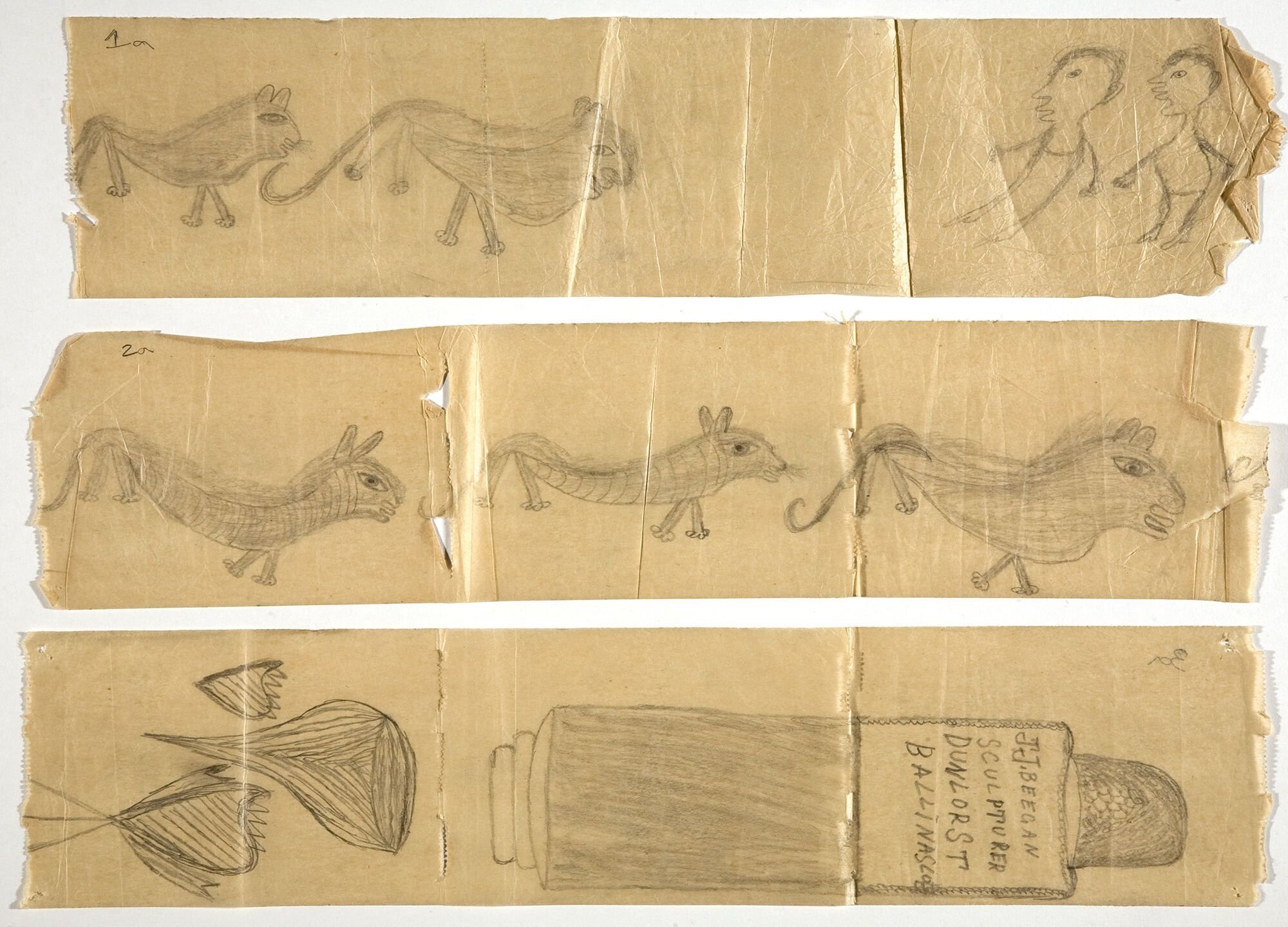

TULCA festival is dedicated to the Ballinasloe-born artist and sculptor J.J. Beagan, who according to Clair Wills’ extensive research, spent most of his life in institutions, such as the Netherne Mental Hospital in Surrey, England. While the decision to not display his work in the exhibition resulted more from logistical than conceptual reasons - his drawings, which are now part of the Adamson Collection, were too delicate to be transported, and instead are printed in the accompanying booklet - it does open relevant questions about the reproduction of medical violence through the displaying so-called “Outsider Art”. Is there a way of presenting a body of work, like J.J.Beagan’s without replicating the pathologizing gaze that perpetuates landscapes of medical incarceration within cultural spaces? To detach the artwork from the clinical language which justified their expropriation, collection, showcasing, and ensuing market value as Outsider Art, seems to provide a first step in changing the narratives attached to his art. Nonetheless, it also demands a shift in the way the works are displayed and perceived because as long as the ways we address, show, and review the art of disabled artists differ from those of able-bodied artists, contemporary art and culture will reproduce these stigmas. Dedicating the festival to J.J. Beagan instead of being about him, celebrating his work rather than pathologizing it, might offer a starting point to break with both the institutional erasure of subjecthood for artists who have been incarcerated in psychiatric hospitals, and of the framing of such artists’ remembrance through art historical categories. TULCA for me is a reminder that a changing of the means of representation is needed to form the basis for rethinking the narratives inscribed into the medical landscape, and onto the bodies that inhabit it. According to Carolyn Lazard: „To commit to disability justice is to redefine the terms of subjecthood“. [10]

I am not a dreg of society

I am a loved and wanted person

I am not a dependent person

I am an interdependent person

I am a skilled poet

I am not a heterosexual woman

I am a survivor in today’s times. [11]

In her opening speech, Iarlaith Ní Fheorais called the festival “a love letter to Galway”. This feels bittersweet when regarding it through the angle TULCA offers. Admittedly, though, this text is a little bit of a love letter itself. One written with a deep appreciation for the dedication to accessibility and disability justice of my dear friend Iarlaith, and for the impressive group of artists she brought together in this festival. What Iarlaith and I share is an abiding interest in the particularities of history in locality, and a persuasion that “the local” can never only be a static, romanticized image.

\\

Feb 09 2024

Theresa Zwerschke

(*1993, Germany) works as an artist, organizer and educator with a specific interest in cultural practices striving for systemic change. Her practice is situated at the intersection of critical pedagogy, artistic research, and socio-political knowledge production. She holds a BA in Art Pedagogy (University of Leipzig), a Diploma in Fine Arts (HGB Leipzig), and an MA from the Dutch Art Institute.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 2007) 8.

[2] Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 2007) 8.

[3] Iarlaith Ní Fheorais, “From Ballinasloe to Netherene: The Drawings of J. J. Beangan,” in honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise (Galway: TULCA Publishing, 2023) 5.

[4] Sami Schalk, “Making Connections: Prisons and Mental Institutions,” in honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise (Galway: TULCA Publishing, 2023) 52.[5] Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 2007) 7.

[6] Mia Mingus, Access Intimacy: The Missing Link, (Leaving Evidence Blog: https:// leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/) last access: 28.11.23

[7] Leila Hekmat, Symptom Recital: Music for Wild Angels, Video, 86 min, 2023.

[8] Róisín Agnew, “The Mental Patients’ Union,” in honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise (Galway: TULCA Publishing, 2023) 39.

[9] Rouzbeh Shadpey, Forgetting is the Sun, Video, 14:34 min, 2023.

[10] Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice (Recess Publication: 2019) 9.

[11] Carol K. Kallend, “The Lone Dreg Seaks Back,” in honey, milk and salt in a seashell before sunrise (Galway: TULCA Publishing, 2023) 17.

IMAGE CREDITS

Cover: Leila Hekmat, Symptom Recital - Luzie Naters, Filmstill, 2023 © Leila Hekmat.

fig. 1: Aisling-Ór Ní Aodha, bless every foot that walks its portal through, 2023 © Ros Kavanagh.

fig. 2: Bridget O’Gorman, Support I Work, 2023 & Philipp Gufler, Quilt #47: Charlotte Wolf, 2022 © Ros Kavanagh.

fig. 3: Anna Roberts Gevalt, Ridgewood Sick Center, 2023 © Ros Kavanagh.

fig. 4: Sean Burns, Dorothy Towers, 2022 © Ros Kavanagh.

fig. 5: Rouzbeh Shadpey, Forgetting Is the Sun, 2023 © Ros Kavanagh.